Cockfighting in the Philippines, locally known as sabong, is more than just a sport—it is a cultural phenomenon, a billion-dollar industry, and for many, a way of life. Despite its bloody and controversial nature, it remains one of the most deeply rooted traditions in Filipino society, second only to basketball in popularity.

Table of Contents

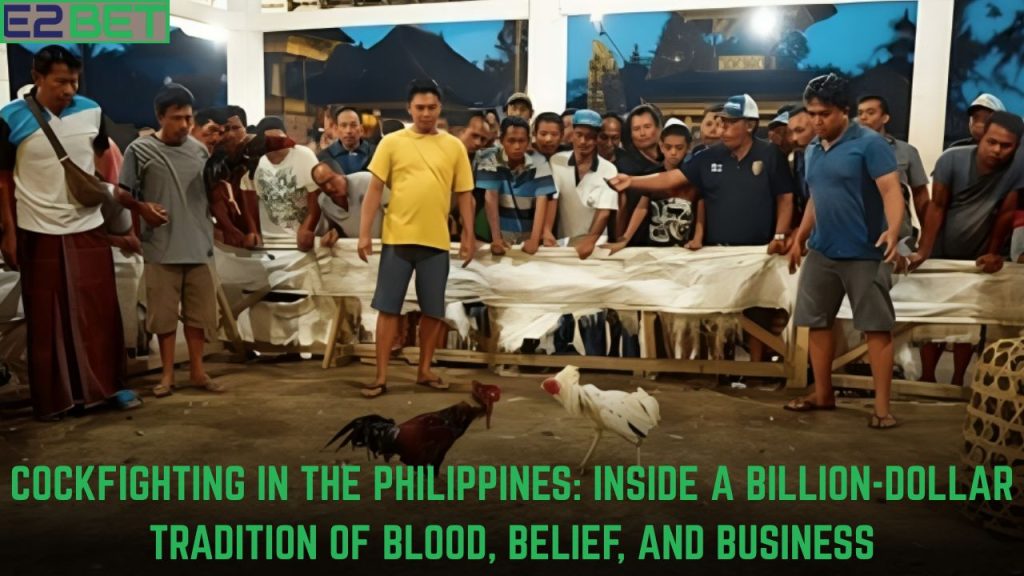

First Glimpse: Arrival at the Roligon Mega Cockpit

On a humid Sunday in Metro Manila, outside the Roligon Mega Cockpit in Parañaque City, the scene is already bustling. A row of black Toyota Land Cruisers and motorcycles lines the street. A taxi driver, smoking with his door ajar, nods toward the entrance with a smirk. A one-legged beggar waits by the door, hoping for a few coins in exchange for good fortune. From inside the stadium, the roars of an eager crowd echo like thunder.

This arena, one of the most prominent in the Philippines, offers free entry on Sundays, drawing spectators like sardines into a tin. The vibe is intense, the anticipation palpable—like stepping into the set of Bloodsport.

The Scale of the Industry

Cockfighting in the Philippines is estimated to generate billions annually. With over 2,500 licensed cockpits nationwide and approximately 30 million cocks killed each year, sabong has become an institution.

Inside Roligon, I’m greeted with suspicion from security guards eyeing my camera gear.

“Are you from an animal rights group?” one asks.

Photography is often restricted—not just because of ethical concerns, but because many breeders hail from countries where cockfighting is illegal. After clarifying that I’m a photojournalist documenting the tradition, they let me through.

Legal vs. Illegal Arenas

While the Philippines has legalized and regulated cockfighting in licensed venues, underground matches—especially in Metro Manila’s shantytowns—remain common. But the real money lies in the legal arenas, particularly in VIP sections known as “preferencia”, where high rollers bet hundreds to thousands of dollars on a single fight.

Behind the Scenes: Breeding and Ritual

In the weigh-in area, I meet Albin, a 57-year-old breeder from Bacolod City, known for producing strong, resilient fighting cocks. He’s brought one of his six trained birds to compete. Each match-up is based on weight and wingspan. After matching, a specialist known as the “manari” attaches a razor-sharp blade to the bird’s left leg—a deadly extension designed to end fights quickly.

In the Ruweda (cockpit), around twenty men sit silently with their birds—focused, anxious, and proud. Albin mutters nervously, “I think this will be a winner.”

Months of preparation—strict diet, training, and rest—are reduced to just a few minutes of brutal combat.

The Betting Ritual

As the casador (matchmaker) announces the bout, the arena comes alive. Cocks roam freely for spectators to assess. Betting begins with bettors signaling their wagers through Kristos, intermediaries who use a complex language of hand gestures:

- Fingers up = 10 pesos

- Fingers sideways = 100 pesos

- Fingers down = 1,000 pesos

Eye contact, finger signs, and trust replace any formal betting slip. After a few minutes, the casador calls for silence: “Larga na!”

Blood on the Dirt

The birds are released. Within seconds, the fight begins—ferocious, fast, and lethal. In less than a minute, Albin’s cock stands victorious. The other lies dead on the cold dirt floor. The referee’s decision is final, and Albin raises his fist in triumph.

Around him, the crowd reacts with cheers or groans. Some win a small fortune, others lose a week’s pay. A cleaner sweeps away blood and feathers, while the loser’s body is carried off in a plastic bucket—often to be cooked and eaten by the winner.

Aftermath and Care

Albin’s cock, though victorious, is wounded. A cock doctor stitches its wings and chest for a few hundred pesos. If the bird dies, no fee is charged.

Cock care today is as scientific as it is traditional. Breeders use vitamins, vaccines, steroids, and even testosterone to enhance performance. Superstitions still linger too—some believe a cock should touch a virgin’s underwear for good luck or avoid being touched by a menstruating woman or a widower.

Gender and Culture

Arenas are almost entirely male-dominated spaces. The few women present typically sell snacks and drinks. As one old saying goes, “A Filipino man loves his cock more than his children”—a quote famously attributed to national hero José Rizal.

Even the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos saw the cultural significance of sabong, passing a law in 1974 declaring cockfighting a protected national heritage.

Global and Historical Context

Evidence suggests that cockfighting may be one of humanity’s oldest sports, with origins dating back thousands of years in Southeast Asia. In Bali and northern Thailand, cockfights still play a role in religious ceremonies, often involving blood rituals to honor ancestors or spirits.

As chickens became more abundant, so did their use in both spiritual and gambling practices. Some scholars even argue that cockfighting contributed to the domestication and global spread of chickens—now the most consumed protein source on Earth.

For Glory or Tragedy

In the slums of Manila, cockfighting offers a chance for upward mobility. A winning bird can bring honor, status, and money. But for the vast majority of birds, the dream ends in the dirt of the Ruweda.

For breeders like Albin, each fight is a gamble of hope and heartbreak.

Final Thoughts

Cockfighting in the Philippines is layered—equal parts sport, spectacle, business, and tradition. It is brutal, controversial, and mesmerizing. Whether one sees it as cultural heritage or cruelty, one thing is certain: it reveals the complex intersections of belief, survival, and human nature in one of Southeast Asia’s most vivid and enduring traditions.

Cockfighting in the Philippines

| Topic | Key Points |

|---|---|

| Cultural Role | Sabong is a traditional and widely accepted national pastime in the Philippines. |

| Industry Scale | Generates billions annually with 2,500+ legal arenas and mass participation. |

| Legal Status | Legal in regulated arenas; illegal matches still occur in urban slums. |

| Breeding & Rituals | Birds are trained for months; mix of superstition and science in preparation. |

| Betting System | Bets placed using hand signs via “Kristos”; no formal slips used. |

| Fight Duration | Most matches last less than 2 minutes and often end fatally. |

| Aftermath | Wounded birds are treated; losers often become food; cock doctors offer care. |

| Controversy | Seen as both heritage and cruelty; remains deeply ingrained in Filipino society. |

Read more:-

- Sweater vs. Hatch: Which Bloodline Dominates the Pit?

- World Slasher Cup Champions: Gamefowl Bloodlines That Win Fights

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Is cockfighting legal in the Philippines?

Yes, cockfighting (sabong) is legal in licensed arenas, but illegal fights still occur in some areas.

2. How popular is cockfighting in the Philippines?

It is extremely popular, considered a national pastime with over 2,500 legal arenas across the country.

3. How are bets placed during a cockfight?

Bets are placed using hand signals through intermediaries called “Kristos,” with no written slips.

4. Do all cockfights end in death?

Not always, but many do. Some birds are treated by “cock doctors” and may fight again if they survive.

5. Why is cockfighting controversial?

Because of its violent nature and animal welfare concerns, it is seen as cruel by some and cultural heritage by others.